A Rory by any other name… Introducing the southaussienames R package

We recently began the process of investigating the impact of gender in our new dataset of Australian film credits and immediately struck an unexpected problem. In addition to the challenges we already anticipated, such as the well-known limitations of trying to approximate gender based on first names there was another, less immediately apparent dilemma. For historical and uneven datasets like ours that don’t contain self-reported characteristics, one of the only ways to gain a sense of how gender might be distributed is to computationally match people’s names to the sex assigned in birth records.

The limitations of this approach to gendering data are obvious (there will always be exceptions, we are only ever gendering names and not people, etc.). But what really struck us was just how US-centric these data matching packages are for names in English-speaking countries during the last century. Once again, Australia’s status as a medium sized, predominantly English-language nation has meant that the nuances of its cultural difference from the US (and historically the UK) are not often supported. Australian baby name gendering conventions, we realised quite quickly, do not always follow US practices (hello Shannon or Harley!).

So after searching for a more local option and not finding one, we created it and have made it openly available as southaussienames, an R package containing public data on all baby names registered in South Australia between 1944 and 2013.

Why did we make this package?

After more than a year spent putting together a massive dataset with the CARD lab detailing Australian film productions and who worked on them, we’re now analysing the historical dynamics of collaboration on Australian feature films. A huge part of telling this story is understanding the social inequities and hierarchies that underpin Australian film production, particularly the dominance of men in the industry. Unfortunately, we don’t have any information on the identity characteristics of the people, we only know the names by which they were credited – a familiar problem in social data science. This leaves us trying to explore what we know about the names of the people, and what this might reveal about the profile of the industry instead.

We want to be clear here that we’re not looking to use names as a proxy for gender, and we’re not encouraging people to use the southaussienames package for that purpose either. Using names as a basis for gender analysis is obviously problematic, for lots of reasons. However, there are tools which have been developed to help researchers do exactly that. Despite the claims they make, these tools can never tell you the probability that a person has a particular gender. Even if they were transparent about the methods and what the results they report represent (which they usually aren’t), the idea that they can accurately “predict” gender is completely inappropriate.

At their most useful, tools of this nature can only tell you about the names themselves and the patterns in the registration records of those names. That’s what packages like babynames and gender offer: a way of querying name registration records, to understand the sexes that are assigned to babies when they are registered with a given name. Again, to be clear (because it’s important): knowing that 99.9% of the babies registered under a name in a given date range were assigned male at birth does not mean that a particular person with that name born in that range is a man, or even that there is a 99.9% likelihood that the person is a man. Such “guesses” about people should not be made, whether based on name or anything else.

On the other hand, while acknowledging these caveats and cautions, names can be relevant and useful sources of information to understand person data. When analysing a population in the aggregate, it would be useful to know (for example) that 80% of the names are registered to people assigned male at birth. This is not a substitute or proxy for knowing the people’s gender, but it is useful information so long as the researcher reports on what it means accurately, carefully and responsibly. As the author of the gender package advises, this kind of approach can be a valid strategy “only when the alternative is not a more nuanced and justifiable approach to studying gender, but where the alternative is not studying gender at all”.

So why not use pre-existing packages?

Names are culturally specific and change over time. Even within a given country, consulting name registration records from 1930 might reveal a completely different picture than consulting the records from 1960 or 1990. This matters for our dataset, because it covers a period of film releases from 1975-2022. Unfortunately, the only data source which might be useful for this period is the Social Security Administration (SSA) dataset distributed by the babynames and gender packages, which describes babies registered in the United States from 1930 to 2012.

We had some concerns over how useful the US-based data would be for our work. There’s a lot of overlap in US and Australian naming conventions, but Australia does have its own peculiarities, as we’ll demonstrate. To try to put some evidence behind these concerns, we set out to find a more appropriate data source for Australian names.

We found some interesting sources in Australia, but nothing as comprehensive as the US SSA data. For example, several Australian states publish lists of the top 100 baby names, but those are not really useful for this purpose. The most robust source that we found is a dataset published by the South Australia government in the form of data files ranking all names registered to babies assigned male and female from 1944 to 2013 in the state.

Comparing the data provided by the South Australia government with the US SSA dataset reveals some of the differences between the two countries. For example, the South Australia data reveals that “Lachlan” was the third most popular baby name overall in South Australia in the year 2000. According to the babynames package’s data, “Lachlan” ranked 5,680th among names in the United States that year.

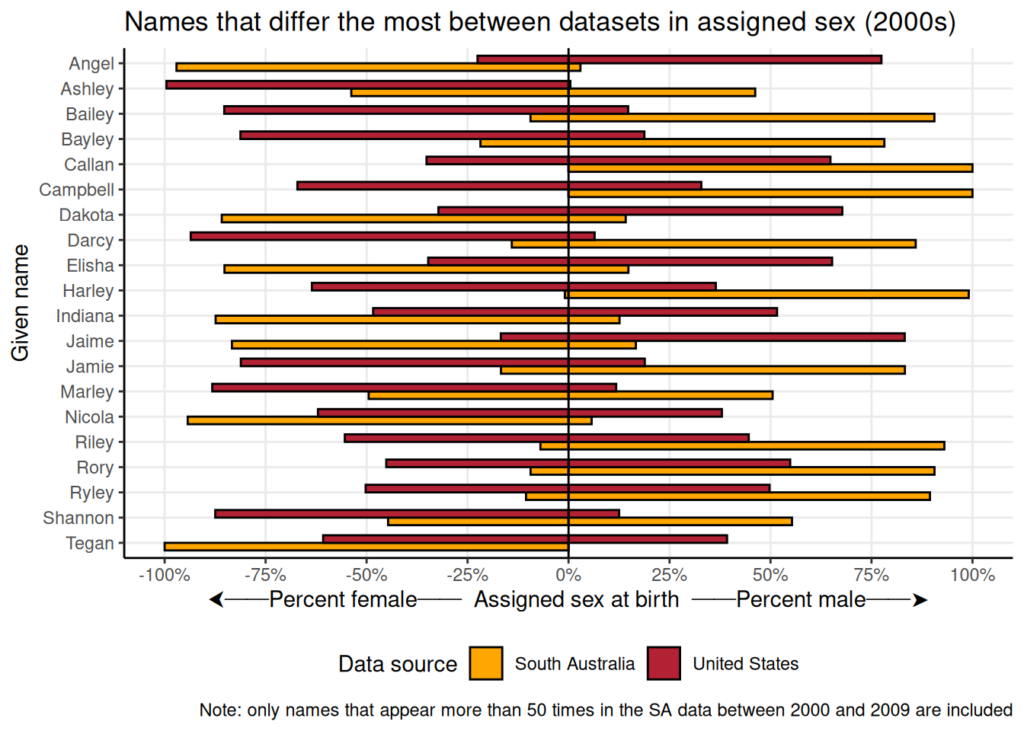

Consider also the following figure, showing some examples of names that had a different assigned sex distribution in the US SSA data and the South Australian data during the 2000s:

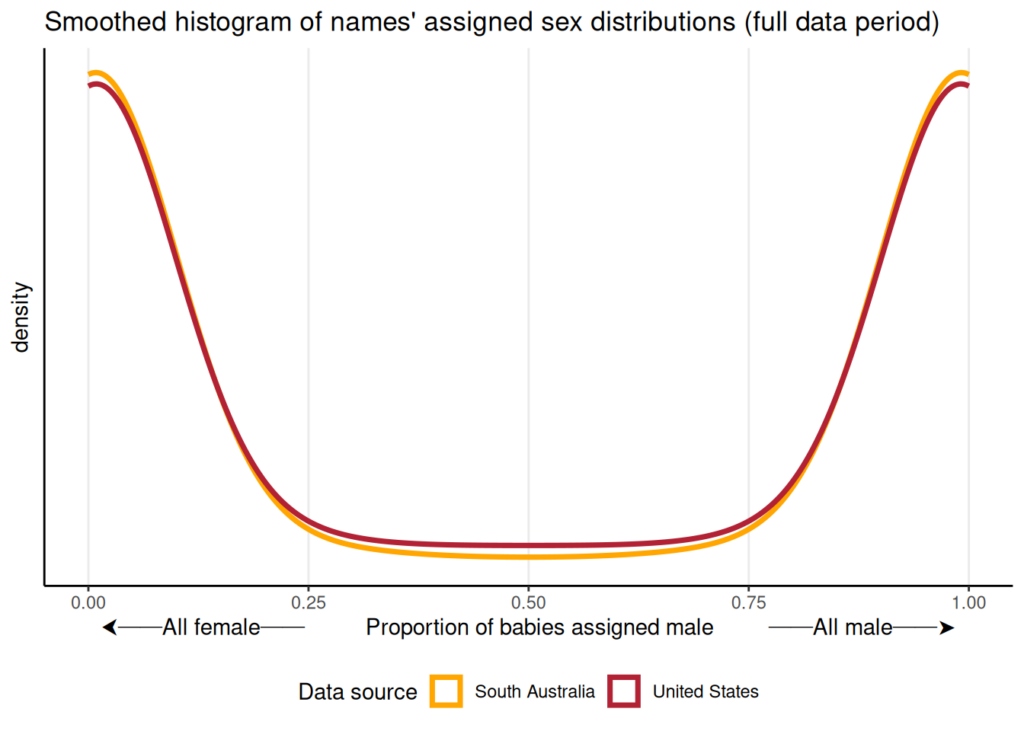

The chart implies that in cases where there is a big difference between the US and South Australian name, it is the Australian cases that are more strictly binary (in the sense that a name is overwhelmingly associated with a single sex, with little ambiguity). However, when we tested this for all the names that appear more than 100 times in the South Australia baby names data, we found that there is little difference between the US and South Australian records.

With a little data processing we were able to set the South Australia baby names data up as an alternative to the SSA dataset and, when we confirmed that it worked as intended, we decided to package it up for others to use as well. The R package presents the South Australia data in a tidy format, and includes a helper function for querying names against years or ranges of years.

What can you use this package for?

We imagine this package will be useful for people working on Australian research that requires some kind of gender analysis and where self-identified gender data is not available. It’s also useful for anyone who wants to explore the patterns in different names’ popularity over time, or build understanding of the differences between (South) Australian names and names from other cultures and contexts. It could even serve as a random name generator for fictional Australian people.

We enthusiastically invite you to use and share the southaussienames R package. Let us know what you discover!